-

Common misconceptions

Before we start comparing signed and spoken languages, it is important to establish that sign languages are in fact 'real' languages.

"Sign languages are just people gesturing at one another"

There are large elements of iconicity and gesture in sign language, but they are incontrovertibly real languages, with phonology, syntax and conventionalised meaning.

"There is one, international, sign language"

Different people groups use different sign languages. As with spoken languages, they may be more or less related to one another: Auslan (Australian Sign Language) is closely related to BSL (British Sign Language).

An international sign language does exist, but then so does Esperanto!

Because sign languages are more iconic than spoken languages, and because signers often have to communicate with non-signers, and because of historical links between the Western sign languages, signers generally find it easier than speakers to communicate with people from a different language background.

"British/American/... sign language is just 'English on the hands' "

There are systems for representing spoken English with hand gestures, just as we can represent it with pen-marks and call it writing. However, these are not the same as sign languages. They may borrow many of the gestures from a sign language, but they borrow the syntax - or even morphology - of English, and lack many of the suprasegmental features of true sign languages: the facial expressions that are the equivalent of intonation and stress in a spoken language.

Modality differences: signed vs spoken

What difference does modality make?

Sign languages use the visual-gestural system, whereas spoken languages use the oral-aural system.

In terms of how we process language, sign languages do make more use of our visual system, but the vast majority of processing is in the left hemisphere of the brain, in the same areas as for spoken languages. (How the brain processes language, and the difference between left- and right-handedness, is entire blog post of its own.)

Iconicity

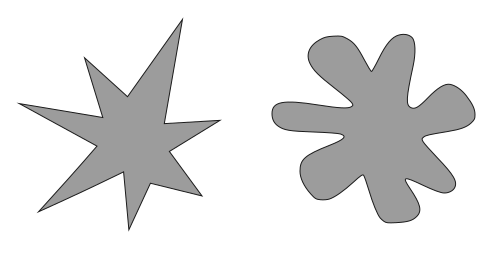

Something is iconic if there is a link between its form and what it represents.Some spoken language is iconic: we have onomatopoeia such as crash, thud, and hiss. These sounds are isomorphic too: "hiss" resembles the sound of a hiss. There is also iconicity in spoken language which is not isomorphic, like the bouba/kiki effect:

|

| Which is bouba and which is kiki? People usually give the same answer, regardless of which language they speak. |

Signed languages are more iconic than spoken languages, for a variety of reasons. Firstly, it is easier to represent concepts visually than orally. Secondly, being younger languages, it may be the case that they will accrue more conventional meanings with time.

However, most iconic signs are not isomorphic. Take the following sign: a gesture of a fist closing, as it moves away from the chin. It is iconic - it resembles a beard. What does it mean?

In BSL, it means "man". That makes sense. But in ASL (American Sign Language), it means "old". That also makes sense.Without learning the conventional meaning in each language, you cannot understand it.

Your options might be more limited than in a spoken language, due to the iconicity: "man" gives you no clues whatsoever. But "that sign probably means something about beards, or pulling, or chins, or maybe something else" is still not particularly helpful!

Does this greater iconicity make a difference? Until recently, it was thought not to - it doesn't affect whether or not you make slips of the hand, or how easily you recall the word. However, a study by Thompson et al. (2012) has shown that it does play a role in acquisition.

Phonology

Signs are not single unified wholes. Just as in spoken languages, words are made up of meaningless segments that combine into meaningful words, signs have meaningless features which combine to make meaningful signs:

- Handshape

- Location

- Movement

- Orientation of hands

These features form minimal pairs. Just as you can change "b" to "p" and change the meaning of the word, if you change one of these features, you have a new sign.

There are a limited number of handshapes and locations which are allowed in a given language, even though others are physically possible. (Just as spoken languages don't use all the sounds that other languages use.)

When words are borrowed from one sign language to another, handshapes and locations are changed, to conform to the phonology of the borrowing language.

Sign languages also use non-manual features: facial expressions and head movements.

Non-manual features in BSL play a similar role to prosody (stress and intonation) in English. They can be used to make lexical distinctions, and indicate topics and questions.

Morphology

Our auditory systems can resolve the order of stimuli separated by 2ms, whereas our visual system needs 20ms (Brentari 1998). The auditory system has better horizontal (temporal) processing, whereas the visual system has better vertical (spatial) processing.

This means that visual-gestural languages must contain more simultaneous information than spoken languages if you want to transmit concepts at the same rate, but they can exploit the spatial layout better to do so.

In spoken languages, morphology tends to be concatenative - you add prefixes or suffixes to words to change their meaning: anti-dis-establish-ment-arian-ism.

In signed languages, morphology can be concatenative, but there is much more simultaneous morphology. For example, signing the number handshapes at the nose, instead of in neutral space, indicates "years-old".

Syntax

Sign languages have the same hierarchical structure that spoken languages do - words combine into phrases, phrases combine into sentences. They share the same distinctions between nouns and verbs. (There is a lot more that could be said about the syntax of sign languages, but I am not a syntactician.)

Sign languages use something called proforms, which are a little like pronouns in spoken languages. Nouns in sign languages are divided into classes - like Bantu noun classes, or Chinese counting classes - which are associated with a particular proform. Instead of repeating the sign for "man" every time the word comes up, you can simply use the proform for "upright being" after the first time.

There is some debate as to whether any sign language has a basic word order, or whether they are better described as topic-comment languages. Either way, they have very free word order, because they are highly inflectional - like Spanish, and other inflectional languages.

Acquisition

Assuming that infants are exposed to sign language the same way that they are exposed to spoken language - through native speakers from birth - they follow very similar patterns of acquistion.

First, they go through a babbling stage at a similar age. They use a limited range of handshapes repetitively, in neutral space or on the face or head.

Signing infants produce their first words around 2 months earlier than speaking infants. This is probably because the fine motor control needed for speech takes longer to develop.

However, both signing and speaking infants hit the two word stage at around the same time.

In the same way that speakers use Infant Directed Speech - talking more slowly, with exaggerated intonation (see my post on speech segmentation) - signers use Infant Directed Sign. It is slower, and takes place away from the body until the infant learns to look at the signer. Facial expressions are not introduced until infants have acquired signs that need them.

Unfortunately, many deaf infants are not exposed to sign language until they begin school, some 4 years later than is desirable for acquiring a native language.

Conclusion

Similarity between signed and spoken languages is greatest in syntax - the most abstract domain of linguistics - and smallest in phonology, which is obviously very closely linked to the mode used.

There are many subtleties to the similarites and differences between the two modes which I have not discussed, some because they involve in depth discussions of linguistic theory, and some because there are still disagreements about what is and is not linguistically universal.

Politics plays a part here, as everywhere - academic politics, to do with how which theory of linguistics you follow, and broader politics, to do with the status of sign languages, and hence of the Deaf community. The dismissal of sign languages as 'not real languages', which has caused quite a lot of harm, has led to years of proving the similarites with spoken languages. It is only more recently that studies of the impact of modality on language have been more widely explored, and there is still some concern that misunderstanding of the results may cause harm to the cause of native signers who wish to use their language as they see fit.

References

For an excellent introduction to sign language linguistics, which requires no prior knowledge of either linguistics or a sign language, see Johnston and Schembi's Australian Sign Language from Cambridge University Press.

Thompson, Robin L., David P. Vinson, Bencie Woll, and Gabriella Vigliocco. The Road to Language Learning Is Iconic Evidence From British Sign Language. Psychological science 23, no. 12 (2012): 1443-1448.

Brentari, Diane. A prosodic model of sign language phonology. MIT Press, 1998.

Thompson, Robin L., David P. Vinson, Bencie Woll, and Gabriella Vigliocco. The Road to Language Learning Is Iconic Evidence From British Sign Language. Psychological science 23, no. 12 (2012): 1443-1448.

Brentari, Diane. A prosodic model of sign language phonology. MIT Press, 1998.